Date: 18th November 2020

To watch the recording click here

Register to download the webinar presentation.

Transcript

Failure to Thrive: Rehabilitating Long-Term Care

Irving Stackpole

My hope is to further the dialog about long term care in the United States and the U.K. The title, “Failure to Thrive” is an homage to one of the important papers in the sector published in 2014.In the long-term care sector, failure to thrive generally describes a complex array of chronic conditions which in an aging person result in a deterioration and a general failing in health. I believe that that situation describes what’s occurring in long term care very accurately. What I’d like to talk about today is the current situation as well as what might happen regarding recovery.

The news about long-term care hasn’t been good, and continues to come in in pretty difficult tranches. This was an article from one of The New Yorker magazine supplements, The Intelligencer, American Nursing Home Design Is A Failure. While I disagree with the glib nature of the article, I must say that it’s generally not untrue. What we’re going to talk about: structures, programs, technology and information systems, means of production, which in these markets means labor, culture and outcomes. We’re also will talk a bit about the economics of long-term care, and how they are impacting this failure to thrive.

This is nothing less than a crisis. A crisis, of course, is an adverse event which has an impact on your brand and the brand, long term care, the brand, congregate care, nursing homes, all of these brands are being damaged badly in the current pandemic and the aftermath. (See our webinar on Crisis Communications.) The question, of course, is what we can do to save and salvage what we can from the sector. Now, for those of you who are in long term care and in particular in the nursing sector or the care home sector, nursing homes in the US, care homes in the UK, what you’re wondering, of course, is whether the market will recover.

Of course, the answer is, it will. There are durable segments to the long-term care markets and these are in the skilled nursing and nursing home environment. The durable segments are those consumers who have no choice. These are individuals who are poor, very sick, often with neurological or neuromuscular diseases or with memory loss such as Alzheimer’s or cognitive impairments that that are not dementia (CIND), these individuals will continue to require congregate care. So, these segments aren’t going to go away any time soon. For assisted living and home care, these segments are having a different reaction and different consequences from the pandemic. For many assisted living residences, the intake has stopped, and the departures have slowed. So, there’s some stabilization there. I’ve even talked to some clients who have reported to me that they are admitting consumers to their assisted living residences. I think these, however, are the exception rather than the rule. Home care, on the other hand, is indeed experiencing a very serious, very significant growth in interest. The limits in the home care environment are the staff (or to put it differently, “the means of production”).

The real question with home care is labor and the means of production. The other thing that we’ll look at is the likely recovery models. We have done some mathematical modeling to show what we believe will be the recovery rates and patterns in both skilled nursing, nursing homes and assisted living. The recovery, the actual recovery in the sector depends to a large extent on the depth, length and the shape of the public health and economic recovery from the pandemic. I think we have two basic scenario options, and I’ve reviewed this in my prior programs, which I hope you will access as well. One is that the sector will be rebuilt and recharged. Certainly, we see some signals of that, although after working in this sector since 1985, forgive me if I’m a little skeptical. The other scenario is that this sector will be further ravaged and relegated, further neglected politically and used as a football. This in large part what the design article in The Intelligencer is about; that long term care – congregate, long term care and in particular nursing homes in the United States were the result of a collision between poor policy choices in the mid 1960’s era construction and real estate profiteering.

I commend this article to you. It makes for tough reading. I don’t agree with all of the things that the authors were stating, but it is indeed a sobering look at the dimensions of the problem.

On the other hand, we have other voices, like David Grabowski from Harvard School of Public Health, for whom I have enormous respect, saying that we can look for big, big changes to the nursing home regulation as a result of the pandemic. Well, I have a couple of questions about that. First is, let’s define “big”. I may have a very different idea of what we mean by big. I’ll introduce some changes later in this presentation, which I would suggest are big. Then there is the issue of nursing home regulation. Now, it’s been said, and I believe this is true, that nursing homes are more heavily regulated in the United States than nuclear power plants.

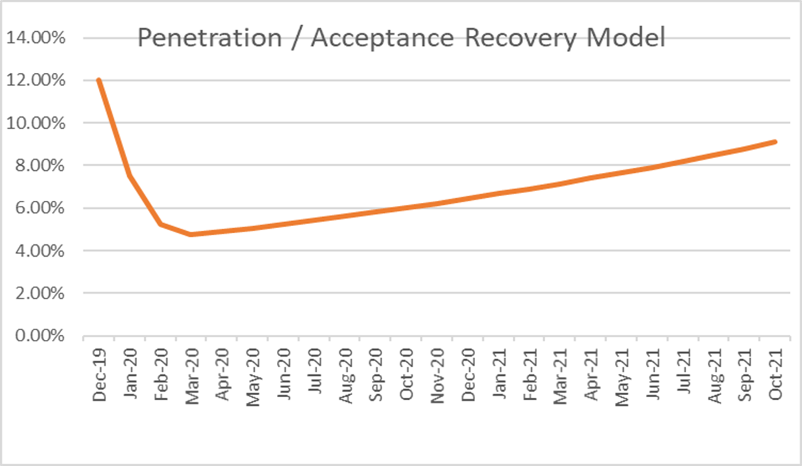

I’ve certainly seen the shelves of regulatory manuals on my client’s offices, bookshelves, and each of them has some element that needs to be observed. It doesn’t make a shred of sense to me to take a sector that is fundamentally on the brink of collapse, and to add more regulation. In fact, if anything, we need to remove regulation and more carefully evaluate what can and should be done to save the sector. Well, I’ve promised some arithmetic or mathematical reviews of what I believe will be the recovery pattern for skilled nursing. This is what I believe it is.

Penetration is a proxy for acceptance and refers to the proportion of the age-qualified population that is using this service. SNF penetration rates in the US before COVID-19 among the aged population cohorts was roughly 1.6%. It was lower in the UK. It’s hard to estimate current penetration rates but there certainly lower than they were in December 2019, and with the on-again, off-again public health restrictions in many communities, it will be sometime before were able to get a stabilized reading. But we certainly have lost utilization and psychological/behavioral “acceptance” of nursing homes in both the US and UK.

The question is whether we’ll ever get back this demand in the markets’ acceptance of skilled nursing. With assisted living, the pattern is different. There will be a recovery.

There will be a loss of confidence, loss in trust and loss in market voice or market share for the sector. But that will be by locations, marketplace by marketplace, and very much driven by how managers in those marketplaces handled & responded to this particular crisis. The domains I’d like to talk about here are the physical structures, the programs to the built environment, the programed environment, technology and information means of production, which here means labor, culture, outcomes and economics first to structures. (The original “PPE” was property, plant and equipment.)

Most of the nursing homes in the United States were built between 1960 actually 1970. They were modeled after Hill-Burton hospitals. They were modeled on hospitals, that is with long straight corridors, efficient for the caregivers, but not very attractive for the consumers. Assisted living, on the other hand, is relatively new construction, new product in the United States and in the UK. So, the product is newer, and it attracts a market rate consumer and family member. The assisted living market started in the early 1990s. Since then, especially in nursing homes, there’s been little or no re-investment in the physical structures. Capital has been extracted, meaning that the capital formation, which has occurred in the sector, has not been re-invested in the sector. Money has been removed, from the sector through a variety of mechanisms, while the federal government has withdrawn fiscal support.

The federal government supports the sector, the nursing home sector in particular, through the Medicaid program and the assisted living sector, partially through the Medicaid waiver program. The federal government pretty much washed its hands of long-term care decades ago when it realized that, based on the trajectory the sector was on it was deemed too expensive. So about the design of nursing homes, capital reinvestment and remodeling, let’s agree that it’s a failed design model. My question here is, would you stay in a Hilton that hadn’t been renovated for 40 or 50 years? Well, no, you wouldn’t unless you had to.

So what do we need, first of all, we need a wide array of new, purpose-designed physical structures to accommodate the needs and preferences of many different populations, the population that should consume and would consume. Congregate senior care is not a monolith. The markets are segmented groups of individuals and most of the marketplace areas, some of whom prefer large buildings with many units, and some prefer small buildings with only a few units. There’s been a call recently for smaller structures, mostly in the wake of the rapid movement of the coronavirus and the pandemic, the infectious disease through congregate care centers.

There’s some evidence to back up the suggestion that, with smaller properties, infectious diseases move more slowly through the population. While that’s true, it’s very, very difficult, as many of you know, to make these numbers work. A big part of the work that Stackpole & Associates does is around market analysis and feasibility studies. It’s very difficult to make small unit like Green House model, assisted living or skilled nursing units work financially. Large structures, like college dormitories with attractive common spaces will be appealing to certain psychographic segments. Medium size, like assisted living residences, will appeal to other market segments, and small buildings, like McMansions with a few unrelated individuals (think Golden Girls) will appeal t still others.

Supply studies in assisted living and independent living usually benchmark what the competition is perceived by the developers as doing. Too often, supply studies neglect the qualitative aspects. Quantitative analysis, or what can the investors extract, doesn’t look at what investors can contribute. The real estate markets undergird this sector, so the questions are, “What can we do in the sector, so that the proceeds from investments stay in the sector?”

The other issue from a design point of view is the infrastructure, and specifically telecommunications and the information infrastructure, which is extremely poor in the vast majority of nursing homes. These infrastructure components are better in most assisted living residences, but the deployed technology certainly lags. The critical issue here is access to capital. Who can afford this upgrade technology? Only organizations which can access capital. In the current environment, with occupancies down, with the admissions slowed to a creep in most locations, accessing capital promises to be even more difficult in the near term. We could watch these patterns working out, working themselves out in the capital markets as well. Why don’t we get what we need? Well, first of all, we need a new federal Hill-Burton Act, which was a way to make healthcare infrastructure available across the United States, and it succeeded. There’s no reason we can’t do something similar at this time.

There is an opportunity here to carve out some pieces, to give access to capital so that nursing centers in particular, and even assisted living residences can rebuild to better accommodate the populations that are with them now and are waiting in the wings. The other reason why we don’t get what we need is that the existing operators have a pattern of competing with each other. There’s little collaboration state to state, with the operators going to policy makers in order to plead their case for what’s needed. I’m not talking about a day on the Capitol Hill sponsored by The American Health Care Association, or LeadingAge, pleading for more money. Once the bleeding is is over, what we really need is a collaboration, a cooperation to focus on what we need. I’m going to talk further about that. In addition to access to capital. The sector has historically focused on profit, not the future.

Many of you are dealing with existential threats to your operations. The days cash on hand is measured in a few days among the most operators in the sector, according to several studies. This is a pittance compared to what it is in many other sectors. What this means is that nursing homes and assisted living residences, but nursing homes in particular, have very little resilience for such a supply and demand side shocks as we’ve experienced.

Finally, without collaboration and cooperation in the sector, market communications have been left to individual operators. The net result of this situation is inconsistent and unclear messaging, and confused consumer. We have done a very poor job in the sector, explaining to consumers how to navigate this incredibly complicated long term care system. We’ll talk further about that. In terms of what I think we can do, that’s truly disruptive and a big, big change.

Also, providers don’t bargain together. It’s true that there are associations. There’s LeadingAge, the American Health Care Association, the American College of Health Care Administrators and others. Seldom do we see them truly going shoulder to shoulder and taking a stand on policy issues or taking a stand on innovations which would impact the sector.

I have to ask, having been an employee of an organization that enjoyed the benefits of investment by a Real Estate Investment Trust, “Do we need REITs in the sector at this time?” Is there a way to migrate toward a more reasonable arrangement around how the property is held versus how the operator pays rent?

Next, I’d like to move on to programs the programs in long term care are fundamentally broken down into two verticals. One is location-based programs and the other is need based programs. These are community based, home based, their congregate, their nursing and more their social based. Some of them are in between I-SNPs and PACE. How on earth did it get this complicated? We get calls on a regular basis from family and friends who are confused, don’t know what to do, don’t know how to navigate the system and can’t decipher the language. If the consumers and their families don’t know what they want or need, why aren’t we, the providers and the organizations that represent the providers, why haven’t we been teaching them? Why haven’t we been explaining the difference between home care and the difference between nursing home care and home care, between hospice and home care? Can you get hospice while you’re in skilled care? Can I get home care and then go into skilled care? I don’t understand why these are not being explained through the sector, through the providers, to consumers in the marketplace area. So, what do we need? I’m going to suggest that we wipe the blackboard and focus on three things.

One principle is that we need screening and triage. We need a way to identify what it is that people need, using objective evidence-based criteria and then directing them to those channels so that they can access those services.

The second principle is to fit the person to a program, not the payment. Most people are directed into particular programs based on the coverage that they have, the insurance coverage they have, or the types of payment systems they can access. This to me is completely backwards, and I expect it is to many of you, as well.

The third thing is clear, understandable choices. Credit default swaps are simpler to understand than long term care choices. Maybe we need a movie like The Big Short, which I thought explained credit default swaps quite cleverly, for long term care.

The status of technology in long term care is nothing less than embarrassing, and some of the very early difficulty during the pandemic, and the painful conversations with families about their inability to get information, the outrage in the popular media, the popular press, was based on the inability of the sector to provide accurate information. Long-term care is the sector that modern health care technology left behind. The technology that is in place is focused on recording, regulation and reporting, not on efficiency. Operations that have any technology at all is based on which operators can afford it, so the more upscale nursing centers, the nursing centers that had the better-quality mix, the assisted living residences that had the higher paying populations, they could afford it. So, they had this stuff. The bottom line is that most grocery stores have better technology than long term care providers.

So, what do we need to do with regard to technology in long-term care? The first is we need to have a priority that puts granny over tomatoes. Second, we need to look past things like personal emergency response systems, (“Help. I’ve fallen and I can’t get up!”). That’s just not the kind of technology that’s needed for today’s environment and the legacy based the legacy hospital-based systems are both anachronisms. They’re like rotary phones in the day of mobile phones. What we need is an intranet of long-term care. We need real electronic health records that stretch across and through long term care providers and that connect, through interoperable interfaces, all long-term care providers and I mean all of them; the pharmacy providers, the home health care providers, home and community-based services, housing providers, the DME providers, the physicians, everybody. Then we need to look at something like ambient assisted living and how that will help our seniors gracefully and more healthily age in place.

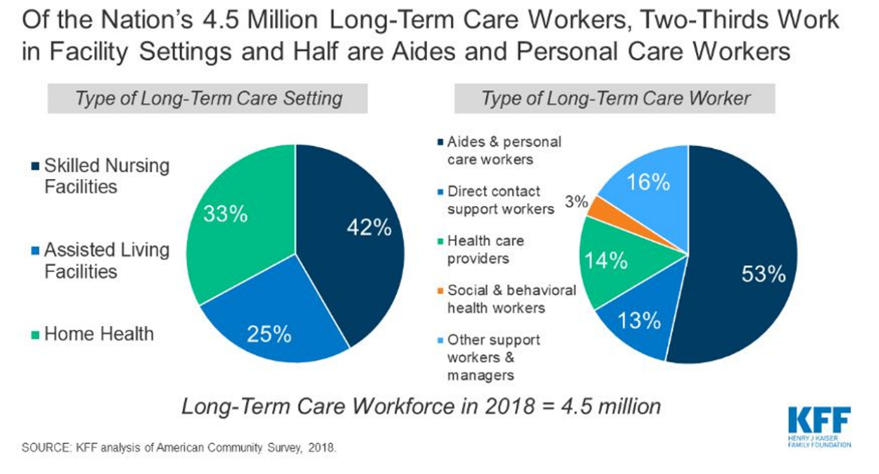

The people question is, who cares? Well, there are a lot of people who do care, and there are millions of non-paid caregivers. The question these days is, “Who wants to work in long term care?” This is an existential question of immediate urgency. We need to be looking at the effects of the pandemic on the sector, on the means of production, and employment in this sector. We need to consider what the sources have been up to this point and what the sources will be in the future. I talked about the means of production or staff serving in long term care before. This is the data from the Kaiser Family Foundation.

Before the pandemic, there were about four and a half million long term care workers in the United States. You can see here how they break down, where they work and the types of work that they do. Almost over 40 percent worked in skilled nursing facilities. It’ll be very interesting to see what that proportion is and how this particular pandemic impacts those proportions.

What’s possible with regards to people and staffing? For the first question, who wants to work in long term care, there really are people who do. It may take a generation to remove the pandemic -related stigma of working in long term care. We should consider disruptive innovations. We need a federal Long Term Care Jobs Act. This would apply federal funds to retrain a sample of the roughly 10 million currently unemployed to work in long-term care. Of course, they should be screened for personality traits, other qualifications and for loyalty, interest in and commitment to the sector. We could use existing job training centers. And salaries need to be subsidized with suitable retention incentives. It doesn’t make any sense to go to the state house and plead for to your Department of Health and Human Services for more money to pay people when they’re churning, they’re coming in and going out. That to me is a very poor investment. I don’t see how public policy directors or politicians are going to sign up for that.

Culture, the culture in long term care has been difficult at best. This is a rather dire picture of an environment in a long-term care center. I’m sure you can all identify with this culture isn’t something that you put on like a Band-Aid over an operation. It’s something that’s grown organically. In all the survey work we’ve done around the United States, we can identify based on leadership characteristics where the culture is apt to increase retention and loyalty among staff, and where it’s a hindrance to loyalty and staff.

Outcomes certainly needs to be considered in the current QAPI environment. The new data requires clinical results, which I would argue is only part of the story. Quality isn’t the absence of an outcome of a clinical intervention. Quality is the degree to which the service is free of defects.

Who determines what a defect is? Well, certainly clinicians are in a position to evaluate whether or not weight gain or weight loss is a defect, but so aren’t the family members. The family members and the consumers themselves are in the best position to tell us if the service we’ve offered is free of defects. In assisted living, it’s common and routine for operators to survey family, residents, staff and to evaluate quality in a rigorous way. This as been done less frequently, less rigorously in nursing homes and other long term care settings. Consumer satisfaction focuses on what the consumers want, what they perceive is their needs and what their families want. If they don’t know what they want,why aren’t we teaching them? This goes back to the first point about damage to the brand and the difficulties around the complexity of programs and long-term care. The sector have done so very little to train our audiences about how to access our services and how to differentiate between what I need today, what I might need tomorrow, what’s good and what’s acceptable for now.

Finally, we come to economics, which is usually where people start, but it’s really at the end of the line.

Basically, the long-term care systems have been shortchanged for 30 years. We in the sector have put up with this in part because we’ve been able to cross subsidize our operations by having a few private pays, and a few Medicare which subsidizes lots of Medicaid beneficiaries. Now that the water has drained away from the stanchions holding up that structure, the rot is apparent, and it can’t continue. Medicaid cannot afford long term care the way it’s currently structured; it’s simply a nonstarter. Medicare backed out 30 plus years ago, and consumers still today think that the government will pay for long term care and. This, in spite of the fact that, in the United States alone, we enjoy almost $500 billion in value for nonpaid care. These are family and friends who care for the sick, elderly person next door across the town or across the street. There’s also waste, maldistribution, lack of collaboration and fragmentation.

All of these things contribute to the crazy cost model in long term care.

Here are some ideas that I want to float in order to get what I think we need in long term care. I believe there’s general agreement about some of these things. My sincere hope is that this presentation, along with prior presentations, is really just the beginning, a beginning of a discussion, a meaningful discussion, not about changing the color of the band aids or rearranging the decks chairs, but really figuring out what it is that we need.

First of all, we need a federal insurance program for long term care. This is not rocket science. Every other OECD country has this. For example, Japan did not. Japan faces an even more challenging demographic cliff than Europe or the United States. Japan introduced long term care insurance in 2010. And if they can do it, we can as well. We need a federal insurance program for long term care. It’s been introduced several times. It’s been talked about. But as I suggest here, it’s always the bridesmaid, never the bride.

It would be funded through a small increase in Medicare payroll deductions and small , means tested premiums. So, this would be small progressive premiums on part A, part C and part D, Medicare. Yes, ladies and gentlemen, this will create a kerfuffle, but we can afford this, really. Also, private long term care insurance should be fully deductible. Private long term care insurance has never reached a penetration above 12 percent in the United States. Its rate is a little lower in the U.K.

There are several reasons for that. Part of the reason is that consumers don’t believe that there is a serious funding gap facing them for either their care in long term settings or the care of their loved ones. Make private long term care insurance fully deductible and we could create, as was done in Japan, long term care risk pools in each state, so each state would have its own long term care risk pool and vet participating, private long term care insurance companies that want to participate. A very similar model to ACA’s state insurance exchanges.

Health insurance providers should spend a small fraction of one percent, about half of one percent of premiums, on education communications to catch up with what the sector hasn’t done to teach consumers and the general public how to access our services, what they need, what’s good about private long term care insurance, what’s available through public long term care insurance, and what their options are in terms of private programs and needs. So that when my mother falls and breaks her hip at home, the daughter isn’t calling around frantically. She knows who to call. They know what to do because they’ve heard about it. Their friends have talked about it. They’ve talked about it at dinner parties, (if we ever get back to having dinner parties).

I think the next step is to look past the current situation, and accept that congregate long-term care, especially nursing homes is a complete design failure. So, the next step is to look at a community of action. It isn’t just policy makers. It isn’t just providers. It isn’t just people in the government. It’s all of us. We need to address this. The consequences of not addressing it are relegation and a very, very bad situation. They’ll be hundreds, if not thousands of nursing homes that will go bankrupt when the pandemic relief cash runs out and they don’t have any consumers knocking at their doors. We need an effective dialog that includes all options, looks at the options and sorts them out at both a state level and at a federal level. Washington State has introduced long term care insurance – public long term care insurance. Let’s look at that model, see how it worked.

Let’s look at the Japanese model. and ideas for what might work in the United States. And frankly, ladies and gentlemen, that’s what leaders do. I’m calling on all the leaders and LeadingAge and American Health Care Association, the American College of Healthcare Administrators, to step forward to engage in these conversations and to move the sector forward. The world we have created is a process. It’s a result of our thinking. It can’t be changed without changing our thinking. There are no scapegoats. We arrived at the current situation through a series of well-intentioned, individual decisions, a series of hundreds, maybe thousands of decisions about coverage, benefits, inclusions, exclusions, payments, funding, good research done, crummy research done. We’ve gotten here through these decisions. We need to accept that, and move on because the future without serious, significant change in long term care isn’t very attractive. Ladies and gentlemen and many of us are going to look to a system that either isn’t there, is too unaffordable or is, frankly unacceptable.

So, with that, I’m going to thank you all for participating.

Questions & Answers

QUESTION: Firstly, OK, what about staff shortages? How can we recover from these?

What a good question. So, staffing in long term care has been a problem, and historically before the pandemic and during the pandemic, the pattern of staff who are very overwhelmingly women, many of them are immigrants, many of them work multiple jobs, including multiple jobs in long term care. These caregivers went from building to building or from home to building back to home and served as vectors for the illness, for the SARS-CoV-2 virus. What we need is we need a model that can replenish the supply of staff, which has been dwindled, and we need to do it very quickly. The most immediate source that seems available to me are the unemployment rolls. There are currently over 10 million individuals who are still unemployed, and I believe that they could be accessed for service in this category. There are some initiatives around this, I believe, in Connecticut, for example. There are now stipends available for individuals who choose to work in long term care. I don’t know whether the stipends go directly to the individual worker or to the operator. But these factors need to be sorted out and it will take a concerted effort on the part of operators, the unemployment benefits team in the state, as well as the leadership organizations, the American Health Care Association, LeadingAge and other groups whose interests should be in meeting the needs of frail elders in their communities. I hope that answers the question.

QUESTION: Will families ever recover their trust of nursing homes after covid.

That is a good question. I’ve tried to model this in my recovery models for the feasibility work that we do at Stackpole & Associates, and we think there will be a range – some families in some marketplace areas will recover trust very quickly in other marketplace areas that have been more heavily impacted will recover more slowly. I think there are quite a few people who need long term care. My hope is that by addressing the staffing shortages, funding requirements and other factors, that we will restore and renew long term care in our communities and thereby restore trust in our providers.

QUESTION: Is there the political will to make the change that you have outlined?

That’s really a question. Is there political will? I see it in some places, and I don’t see it in other places. My overall take is that there is not. There was a presidential commission, a blue-ribbon commission appointed to look at the impact of the novel coronavirus in long term care commission, issued a 186 report. Of that, there was 1 ½ page, double space set of recommendations. Those recommendations were not very disruptive, not very challenging, and I think somewhat politically correct. Now, if you were on that commission and you’re on this call, I apologize if I’ve got your nose out of joint, call me afterwards and we’ll work it through. The report is available and don’t take my word for it. The report is available on our website. Look on the resources page and you’ll see it there listed. I don’t know that we have in the United States the political will to deal with this. My fear and my concern is that we will end up with a sector that has a huge hole in the middle of the United States where those individuals, sadly have to travel hundreds, maybe more miles to find a suitable, adequate long-term care congregate long term care solution, their family member. That would be just not a good outcome.

QUESTION: Please expand on your recommendation on tax deductions for long term care. Especially in light of the current insurance policies.

So the tax deductions on long term care insurance, private long term care insurance, those premiums are tax deductible for most people, but unfortunately, that was a battle that was fought long and hard. And as best I understand it, the people who launched that battle were from the long-term care insurance industry. The battle didn’t succeed quickly so that many of the people who attempted to buy long term care insurance weren’t initially able to deduct all of the premiums against their income or other earnings. Because of that, the general understanding became that these premiums are not deductible, the long-term care insurance business.

Also, there was a flaw in their model as well, the major long term care insurance providers in the United States. I can’t speak to the ones in the U.K. I’m just not familiar with them. But the ones in the United States got the actuarial model wrong. Because of that, their loss ratios were unacceptable and so many of that health and long-term care insurance providers have withdrawn from markets. The cost of staying in the long-term care insurance market is high. The benefit to the insurance providers is relatively low. So many providers have folded up their tents and gone home. Part of the reason for this is the lack of understanding in the general population about how to access services, the long-term care insurance market tried to educate people to raise the issue, the prospect of how they would care for themselves or their loved ones when the need occurred, as they got older and did not succeed. Not enough was invested in it. There was no collaboration, coordination, except perhaps with AARP, to speak of. So those markets didn’t get the kind of penetration that would have helped significantly to keep those players in the game and to help orient the consumer market in the United States as to what a long-term care insurance policy is and what it covers. So now we need to take a really disruptive new approach.

QUESTION: So next one is what can consumers do to promote political will?

There are roughly 15,000 nursing homes in the United States there are roughly (or there had been) about 1.5 million consumers resident in those nursing homes. If every single one of their families and friends were mobilized, that would represent a significant force against the political neglect and political indifference that currently exists, and I should caution that, or qualify that statement, the political indifference of political neglect, this is historical right now. What we have is mostly hysterical. Everything’s going wrong in long term care. Forty two percent (42%) of the fatalities in the United States occurred in congregate long term care settings. This is raising everybody’s concern. What there isn’t is a groundswell from the population most affected toward the political leadership to create meaningful change. You can’t just motivate somebody without giving them a direction. A directionless, motivated person is dangerous. So, we need to give people direction. I look to leadership in organizations, even as commercial as AARP, but certainly the long-term care associations, the organizations that represent the providers and the caregivers. There’s a good 15 or 20 of them, which, if they coordinated, could agree on a cause, agree on a message, a bit of political rhetoric and a program that could be brought to state and federal legislators, especially with some elections coming up that could have a real impact. So, I believe twofold – one, the leadership in the sector. And second, motivating, mobilizing and providing a direction for a groundswell of activity among consumers and their family members.

QUESTION: Would you agree that the root cause of these problems is ageism?

I think ageism is certainly a part of it. Ageism is baked into so much of what we do. It’s extremely difficult to identify it. It’s one of those intrinsic biases which soak into many, many things that we do. Yes. I believe and this may come across as harsh, I believe, that if you’re old in the United States and the U.K., if you’re old and you’re poor and you’re somewhat disabled, you are immediately placed in a lower class. You are discriminated against at multiple levels, at multiple touch points along your journey of life because of those three factors alone. That, to me, is an ethical issue, a moral issue. But importantly, it’s a strategic economic issue. It’s a mistake of the first order because those three pieces, I would call them neglect, those three pieces of neglect are expensive and damaging to the very fabric of society. So, yes, I think ageism is one of the root causes, but it’s not the root cause of how we got to where we got today.

QUESTION: US senior living has suffered a disproportionate number of deaths from covid. What does the industry do to prepare for the next pandemic?

There are very, very smart operators out there who understand what needs to be done and who are going about doing it very quickly, swiftly and competently. And I’m absolutely proud to say that I know and work with a number of them. There’s a story about Mercedes Benz in the 19 late 1950s, early 1960s. Mercedes secured several international patents on anti-lock braking, and instead of limiting their use, Mercedes granted anybody who wanted access to those patents, they granted them access, which is one of the reasons why today we’ve reduced road fatalities. Airplanes have anti-lock brakes as do trains. So, the dispersion of that technology was very quick because one organization had the insight and the ethics to say, this is too important to keep to ourselves. Similarly, in long term care, we’re learning lessons about how to manage the movement of people around the building.

We’re learning lessons about how to supply those people with masks and covering what are referred to as personal protective equipment. We’re learning lessons about how to manage a food service food service inside of a congregate care center. It’s extremely important and yet also a potential vector for infectious diseases. There are people who are learning how to do these things, doing very clever things with ventilation and air conditioning and UV lights and much more.

My hope, my initiative, my urging is that all of these are dispersed broadly and not with help by certain operators because they believe it gives them a strategic advantage.

This crisis isn’t a crisis of one operator. This is affecting the entire sector. If we don’t address it in its entirety, it will come back and bite us again. Yes, there will be other infections, maybe not pandemics, but there will be other episodes of contagion. We as a sector really need to be prepared to say, we got this, guys, this is what we learned, and this is what we’re doing. You can trust us. That’s so critical.

Resources

- Williams, B. Failure to Thrive? Long-Term Care’s Tenuous Long-Term Future.

See: https://scholarship.shu.edu/shlj/vol43/iss2/3/ - Stackpole, I. Bridging the Divide: Transitions to Cross-Continuum Collaborations in Healthcare.

See: https://stackpoleassociates.com/transitions-cross-continuum-collaborations-healthcare - Who Cares? The pandemic shows the urgency of reforming care for the elderly. The Economist.

See: https://www.economist.com/international/2020/07/25/the-pandemic-shows-the-urgency-of-reforming-care-for-the-elderly - True, S. et al. COVID-19 and Workers at Risk: Examining the Long-Term Care Workforce.

See: https://www.kff.org/report-section/covid-19-and-workers-at-risk-examining-the-long-term-care-workforce-tables/ - Adoption factors associated with electronic health record …

- www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov› pmc › articles › PMC4316426

- Jan 28, 2015 – Long–term care(LTC) facilities (as defined by the ARRA) are facility types excluded from the incentives including skilled nursing homes, assisted … also a source of statistical interference when ‘meaningful use‘ is assessed.

- Coronavirus Commission for Safety & Quality in Nursing Homes

See: Final Report of NH Commission Public Release Case.pdf

Stackpole & Associates is a marketing, research & strategy consulting firm focused on healthcare and seniors’ services markets. Irving can be reached directly at istackpole@stackpoleassociates.com.